Our economist's insights: the Mid-Year Investment Outlook for Emerging Markets. A record number of countries, home to half of the world’s population, have held or will be holding elections this year. Investors are looking closely to spot the potential opportunities arising from a political shift.

The impact of electoral choices

A record number of countries, home to half of the world’s population, have held or will be holding elections this year. Investors are looking closely to spot the potential opportunities arising from a political shift. Investors responses have been largely muted to the elections in countries such as Indonesia, Panama and El Salvador where they see the ruling parties’ status quo being reinforced. But in India, and South Africa where the ruling majority was shaken, investor sentiment was initially jittery. Calm soon returned. Investors may be seeing this as an opportunity for a broader democratic reform agenda as the ruling parties in India and South Africa will need to work with others. In Mexico, where the landslide victory of the ruling party paves the way for institutional changes, investors want to see how decisions will impact Mexico’s status as an attractive investor hub. Additionally, the upcoming US elections in November will unavoidably have an impact on emerging economies as US policies continue to shape international trade, finance, and security and will in time influence global climate risks.

Undoubtedly, the election results in the larger emerging economies will have an impact on the international community. These emerging countries collectively emit around half of the world’s greenhouse gases. Therefore, electoral choices at the national levels will either accelerate or hinder climate friendly policies with global implications. Climate change and mitigating polices were recurrent promises during election campaigns but are not yet priorities.

Global fragmentation is increasing with protectionism, onshoring supply chains, anti-migration sentiment, and military conflicts. Governments must navigate these challenges and agree on common ground for global initiatives like climate change and human displacement to avoid devastation.

Better-than-expected economic growth

In the first half of 2024, several factors boosted emerging markets economic activity:

- strong global trade on the back of the resilience of advanced economies,

- financing from the IMF which is helping countries with limited access to private capital, including Sri Lanka and Pakistan, and

- a recovering China thanks to the government supporting the property market, allowing better-than-expected growth at 5.3% in the first quarter against a year earlier.

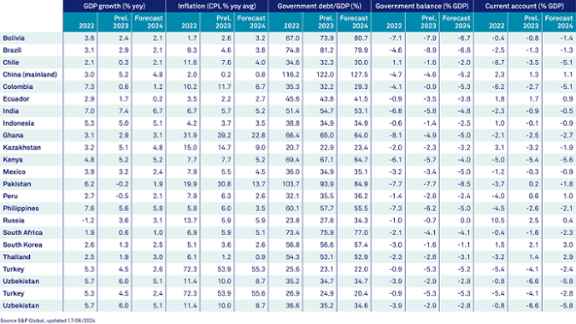

As a result, emerging markets’ economic growth is now broad based. Moreover, the forward-looking economic data like manufacturing surveys remains solid in many emerging economies. For instance, Asia’s new export orders in manufacturing surveys rose further towards its 2021 high. Generally, emerging markets inflation continued to fall in the first half of the year, but the pace of slowdown has been more modest recently. Notwithstanding inflation’s steady decline, there are a few countries with persistent double-digit inflation, including Pakistan, Nigeria and Ghana.

Central banks becoming weary to cut interest rates

Despite the improvements in the inflation trajectory, emerging markets cannot easily decouple from US monetary policy. They remain overly sensitive to US inflation and Fed interest rate policy expectations because of the impact that these decisions have on the US dollar. Indeed, high US interest rates means a strong US dollar and weaker emerging markets’ currencies. This translates into higher import and debt costs when translated into local currencies. As a result, many emerging markets’ central banks remain cautious and are weary to cut rates. Only the more resilient economies with strong international reserves or foreign currency buffers, including Brazil, Chile, Colombia and Peru, have been able to steadily cut interest rates.

Additionally, the effects of high interest rates are still being felt as borrowing rates are renegotiated, or as debt matures and is replaced by new loans. Several countries have recently issued government debt (Eurobonds), including Cote d’Ivoire, Benin and Kenya and this with a higher 'Africa premium'. That is the additional return you can expect to earn for higher risk, compared similar issuers in other regions. Meanwhile governments with high debt levels are in urgent need of a debt restructuring framework, which remains a missing link in debt management and a major cause of debt distress.

Debt restructuring and affordable financing

Countries restructuring their sovereign debts, including Zambia and Ghana, continue to be involved in cumbersome negotiations since there is no well-conceived framework that offers balanced decisions between issuers and official and commercial creditors. Processes are often messy and long. And the longer they last, the larger the material impact on countries seeking debt restructuring.

Both Zambia and Ghana have witnessed a sharp weakening of their currencies since the debt restructuring started. Sri Lanka, also in a debt restructuring process, expects negotiations to move faster with macro-linked bonds as a restructuring sweetener. Creating a just debt restructuring framework is urgent, but equally important is investors’ understanding that most emerging countries need patient capital and affordable financing to develop while avoiding debt distress.

All in all, most emerging economies, despite the high interest rate environment, have shown larger growth differentials when compared to advanced economies. And with some exceptions, emerging markets have managed to bring inflation under control by hiking rates at an earlier stage than major advanced economies.

Countries still need additional investments for climate mitigation and adaptation. Affordable financing from multilaterals, including IMF and World Bank is helping but is not yet sufficient. The International Energy Agency estimates that the public sector will have to come up with about 30% of the climate finance globally needed, and the private sector with the remaining 70%. Currently, financial flows for clean energy investments fall well short of the range of financing needed in emerging markets (excluding China), which is only about 15% of global clean energy investments and concentrated mainly in India and Brazil. This indicates that there is a significant need for private capital that is patient, fair and beneficial for emerging markets.

Elections and outlook

It will take time for the electoral choices and the policies of incoming governments to be rolled out, which will give us a better idea of their implications. Across the world, election campaign programmes have been including climate related themes. During election debates, Indonesia’s largest opposition party promised more support for the energy transition than the incumbent-linked candidate. Indonesia’s newly elected government is likely to maintain the status quo. Claudia Sheinbaum, a climate scientist, was elected president in Mexico. Her academic research explored the energy transition in Mexico, as well as the involvement of local communities in this transition. Even so, her campaign proposals suggested that she will both expand renewable energy infrastructure and support the state-owned oil enterprise. After the elections, we may expect incremental improvements, but private capital will be decisive to get renewable investments rolling.

In the past years, India under Narendra Modi, has shown commitment to achieving its net-zero targets as part of the Bharatiya Janata Party’s (BJP) ruling party’s priorities. Although climate change did not play a significant role during the campaign, the BJP’s election programme emphasised local power generation, including incentives for village councils to install solar grids. Before the elections, Modi ruled almost unchallenged, but now coalition politics will define priorities. Climate policies in Modi’s new term may lose some strength. Meanwhile, South Africa’s worsening electricity and water crises have raised concerns that the country may struggle to fulfil its climate ambitions. In 2023, the ruling party already delayed the decommissioning of coal plants to help ease electricity cuts. And now that the ruling party’s majority has been shaken after the elections, it may be more difficult to shift investments to renewables as investors will seek more evidence of how the new national unity government will work together with rivals.

When populist or autocratic regimes gain power, it is likely that skepticism about their ability to fulfil campaign promises will increase over time.

When comparing democracies to populist/autocratic regimes, the former have proven more committed to net-zero targets than the latter. Therefore, elections are also about shaping our planet. The divergence resulting from electoral choices is an opportunity to piack investments with the righ mix of countries and sectors in line with risk appetite, diversification and willingness to finance change to meet sustainability goals.