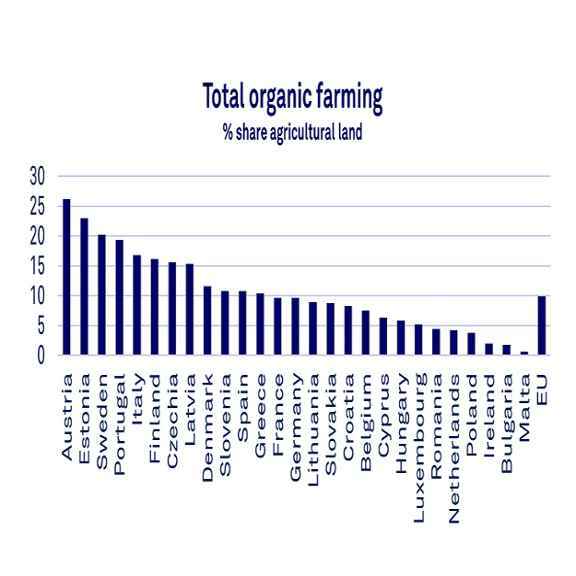

The European Commission’s Farm to Fork strategy aims for 25% of the EU’s agricultural land to be farmed organically by 2030, up from 9.9% in 2021. Although some countries are doing better than others, we are still falling short of this ambitious target. And it’s clear that farmers cannot achieve this transition alone. Consumers have a key role to play in enabling this transition along with other food system actors like supermarkets and suppliers of farming inputs, such as seeds or animal feed.

Prices and consumers

Prices have always played a key role in consumers’ food choices. The prices of organic food are usually higher than conventional food. The impact of this varies among consumers. There are broadly two categories of organic food buyers in the EU: regular buyers and light buyers. Regular buyers are a relatively small and loyal group of consumers that have been buying and eating organic food for a long time and are not as sensitive to prices. They are responsible for about 50% of the value of sales in the EU. The other half of sales comes from a substantially larger group of light buyers, who buy organic food more casually for various reasons. They come from a wide range of walks of life, including double-income households, older consumers and trend-seeking millennials. They are sensitive to prices and consider organic food as a ‘luxury good’. Yet, this consumer group is key to the potential growth of consumer demand for organic food.

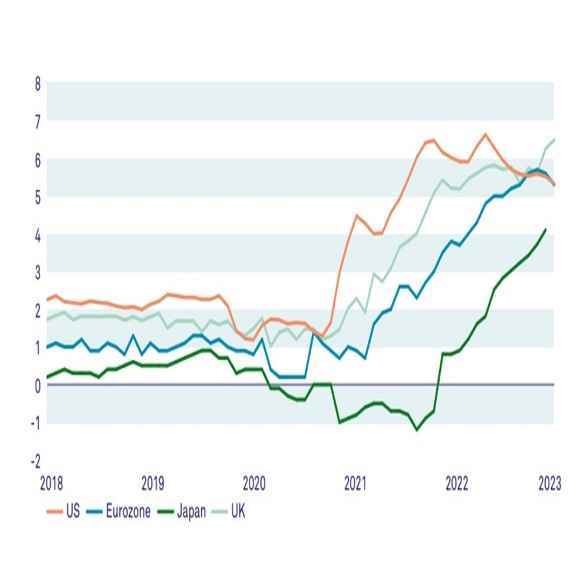

Inflation and organic food prices

Rising inflation since April 2021 has heavily impacted consumption patterns globally. As food inflation surged, organic food prices increased along with other prices. However, in some cases, the prices of goods from conventional agriculture increased more than those of organic products. In German supermarkets, for instance, the price of carrots from conventional agriculture rose by about 20% between November 2021 and November 2022, compared to about 2% for carrots from organic farms.This can be explained by the different cost structures of conventional and organic food. Energy use – natural gas in particular – generates higher production costs for growing conventional food than organic food. This is because conventional food production uses natural gas as both an energy source and as a raw material to produce synthetic fertiliser. Organic food production does not use synthetic fertilisers, but labour costs are higher. It is likely that the sharply risen energy prices in the beginning of 2022 have contributed to price differences between organic and conventional food, although the impact will hit food products categories and European countries differently.

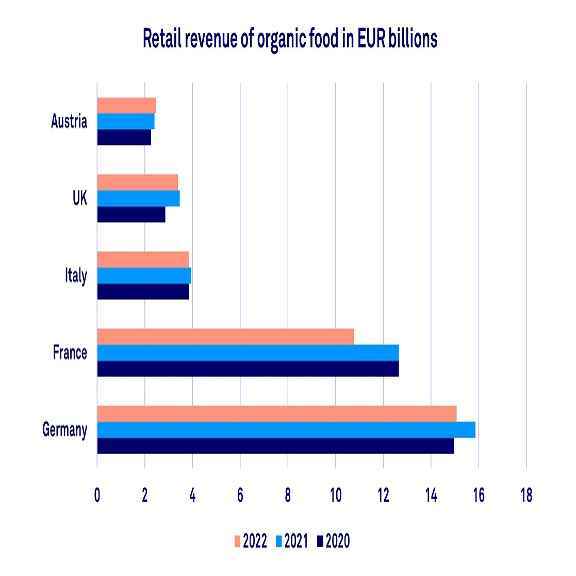

While one might expect this to lead to an increased demand for organic food, its consumption is estimated to decrease by about 5% in EU countries in 2022. According to the US Department of Agriculture, this can be attributed to another effect of inflation: consumers saw their purchasing power decrease. This has led consumers, especially the group of light buyers, to decrease their consumption of organic food. Another key factor is competition by other premium labels like ‘local’ or ‘fresh’. These labels compete with organic food for the ‘light’ organic buyers by speaking to similar preferences such as perceived health or sustainability benefits. This may have played a role in lower organic consumption levels, especially in France.

Given the above, the short-term demand outlook for organic food is not particularly bright. Triodos expects inflation to ease over the next quarters, and nominal wages are increasing considerably, albeit not enough to catch up with past inflation. Even if consumers’ purchasing power is likely to increase, the relative price of organic food is also likely to increase again due to higher labour costs. And although not expected, there is still a small chance of a recession, which would negatively affect purchasing power again. Overall, the economic outlook does not look favourable for a pick-up in the growth of organic food consumption required to achieve the goals of the Farm to Fork strategy. What’s more, surveys indicate that cheaper groceries remain a priority for many consumers, even if they also value sustainability and the quality of food products. While many consumers may consider buying organic and sustainable foods, they need to be mindful of their budgets. So, what can be done to increase the market share of organic food?

Connecting with consumers

Surveys and sales records show that meeting the light consumers on price may help to boost consumption of organic food in the near term. German analysts note that whereas total organic food consumption decreased, organic food sales in budget supermarkets increased throughout 2022, as they gained market share in almost all European countries. The ongoing dedication to sustainability of light consumers can probably be leveraged effectively through budget supermarkets. Supermarkets in general should also be incentivised more to support organic producers, to expand their (exclusive) offering of organic products, and to use nudging techniques to stimulate their customers to buy more organic products.

Platforms like KoRo and Crowdfarming enable the bulk buying and selling of organic food. By leveraging economies of scale, they could help to lower consumer prices while maintaining margins for farmers. Such platform-based distribution channels may also provide long-term support by reaching a new group of customers. A good example of low-cost direct sale is US startup Permanent, which sells wholesale by matching local farmers to large buyers of organic foods, such as universities or hospital canteens.

But as well as addressing the price aspect, the organic food sector should also increase public awareness of agriculture’s enormous impact on the environment, by continuously promoting the good work done by organic farmers and showing the positive impact that consumers will deliver by switching to organic food.

Correcting the price differences in the long term

To level the playing field in the longer term, we need governments to recognise the burden that conventional agriculture puts on the planet. Social and environmental externalities, such as the cost of water pollution, are not factored into food prices. Recently, German researchers estimated that the environmental cost savings from organic farming compared to conventional farming are around 750-800 euros per hectare per year. If governments were to introduce additional taxes on environmental pollution, this would help to narrow the price difference between organic and non-organic food. ‘True’ pricing is key to accelerating the European food transition.

Beyond the pricing of externalities, governments should also support the planetary health dietby establishing subsidy regimes that enable fresh, local and organic food to compete on price. This could potentially provide health benefits to people and help limit negative impacts on the climate, biodiversity, and animal welfare. In addition, governments should stimulate phasing out the most polluting agricultural practices through regulation.

The food transition in Europe requires a strong effort from producers, consumers and governments alike. An important challenge is the comparatively higher consumer prices, currently exacerbated by strong inflationary pressure. In this article, we have described some of the different ways to overcome this challenge. Through collaboration of all stakeholders, the ambitious goals of the Farm to Fork strategy can be achieved and a sustainable and organic food system for the future can be built.