Alejandro Cadena was a year and a half old when he first saw a coffee bean. “My father wrote his master's thesis on coffee rust, a fungus that infects coffee bushes. As a teenager, I helped out at the lab in the coffee region of Colombia every summer, where my father was doing research to improve cultivation.” Years later, Cadena, who was living in London, decided to set up a business with a former fellow student. “We found roasters who said they were interested in Latin American coffee and were willing to pay well, but only for high quality, transparency and traceability,” he says.

The individual coffee farmers are at the start of the coffee

supply chain. Unlike many other crops, coffee is grown on

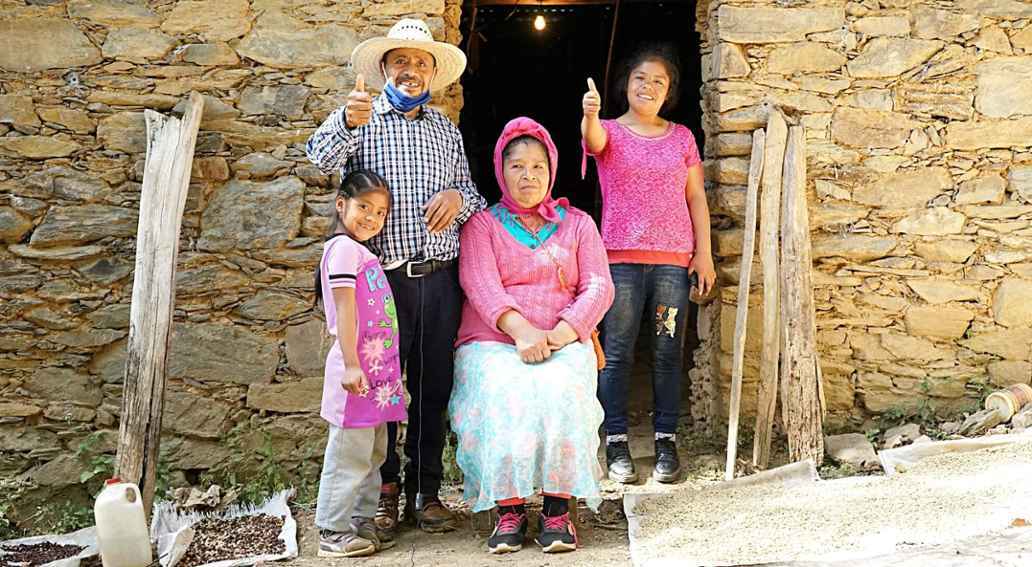

small plots of land. Today, Caravela buys coffee from 4,000

farmers, most of whom have about three hectares of land and

have been in the business for two or three generations. According to Cadena: “What they have in common is that they are extremely committed to their coffee. That's what makes them stick with it, even though it's tough at times.”

Gender inequality

Coffee farmers face many challenges: plant fertility is declining, and climate change is making the weather more unpredictable, which also makes harvests unpredictable. There is gender inequality among farmers (women often have less access to land) as well as an ageing population, as children have often long since moved to the city or abroad for better paid work. On top of that, the COVID-19 crisis is still creating problems in transportation because there is still a scarcity of containers, which leads to long delays. Freight costs have also risen, sometimes tenfold. In addition, Russia and Ukraine are important players in the (organic) fertiliser market, and the war has caused manure prices to skyrocket.

Caravela

Connecting coffee farmers with coffee roasters

As an importer and exporter, the Colombian company Caravela is the link between coffee farmers and coffee roasters. The business started in 2002, and it buys coffee beans from around 4,000 farmers (including 700 women) in Mexico, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, Nicaragua, Guatemala and El Salvador. It has field teams in these countries and sales teams in the US, Australia, the UK and Taiwan. Most of its coffee goes directly to coffee bars, but since COVID-19, it has also started selling to supermarkets and private individuals. In the Netherlands, Caravela works with roasters Keen Coffee (La Serrania Decaf) and Ripsnorter.

All this is happening in a sector that has been virtually unable to provide a living for years anyway. “In the last seven years, the price was so low that it did not cover the costs,” says Nelleke Veenstra, Senior Investment Manager at Triodos Investment Management. “Many farmers have been struggling and are not able to invest in their businesses or their children’s futures. They have lived off the food they have grown alongside their coffee.” Farmers are forced to produce as much as possible in the hope of earning something. This can put a strain on the environment through the use of too much artificial fertilisers and pesticides. And overproduction leads to lower prices over time.

Limited power

What distinguishes coffee from other bulk products, such as corn, soy and grain, is that it is usually grown by smallholder farmers (with the exception of Brazil). You can grow quite a few coffee bushes on a small piece of land. This means that there are no large companies at the start of the coffee chain, only individual farmers.

As a result, they have very little power."Farmers usually have no choice but to sell the beans to the first buyer that comes along," says Veenstra. She adds: “These buyers are often ‘coyotes’, scouring farms and trying to get the lowest price everywhere. Farmers are stronger when they work together in a cooperative, but it is still difficult.” Further down the chain, the players are bigger and more powerful. At the very top are the roasters and supermarkets, some of whom are also roasters. They put pressure on exporters and importers, who in turn put pressure on farmers.

The chain is different at Caravela. The company is both an importer and exporter, so there is only one operator between farmer and roaster. Cadena sees himself as a talent scout. Caravela searches for the best coffee and helps farmers to increase the quality even more so that they end up in a higher price bracket. They are then linked to roasters who establish long-term relationships with farmers and are willing to pay above average prices for the 'specialty coffees': high quality coffee from one region or even one specific plantation.

More than fair trade

Caravela is transparent about the price it pays the farmers. “This is transparency is exceptional, even for specialty coffee,” according to Veenstra. Farmers get between 30% and 100% more than the market average and about 1.5 times the fair trade minimum.

The coffee does not have fair trade certification. Cadena says: "We want to sell something that the market wants, and that people are willing to pay for - then your business model is sustainable. But with fair trade coffee, production far exceeds demand, by as much as double. Farmers must then sell part of their coffee for 'normal' prices. Organic certification is interesting because it provides an indication of quality. And organics is a lifestyle. People remain loyal to it, even when prices go up.” Over one third of Caravela's coffee is certified organic.

If you want to drink fair coffee, fair trade is a good option. The farmer receives a fixed price and a premium for social projects, training and investment. But with Caravela coffee, you also get extra good quality.

Slow drying

Caravela raises the quality of its coffee through education programmes. These differ from farmer to farmer and are tailored to their individual situation. Cadena explains: “We usually teach farmers how to improve all the steps in the process: how to prune, how to deal with diseases, how to plan ahead so there are as few surprises as possible. And how to fertilise effectively. Farmers are in the habit of using as much (artificial) fertiliser as they have available. We help them with a soil analysis so they can fertilise more effectively. Otherwise, some of it will evaporate, which would be a shame.”

The price of coffee

A blessing and a curse

After years of rock-bottom prices, coffee prices have shot up recently due to severe frost and harvest losses in Brazil. Cadena: “In March 2021, half a kilo of beans costs an average of USD 1.20. This rose to USD 2.60 at the beginning of this year. Now we are at around USD 2.30.” Consumers have already seen rises in the price of coffee in the supermarket, and specialty coffee no exception. The current high price of coffee is both a blessing and a curse for Caravela. According to Cadena: “Roasters are used to paying higher prices for specialty coffee, but we can't ask for much more. So now our margins are very low. However, today's high prices are good for everyone in the long run because they set a higher standard. Prices won't go down so quickly anymore. Then eventually we can set a new minimum price. When the market was around one dollar, we paid our farmers twice this, and soon we will increase it to three dollars.” With this money, farmers can make the necessary investments to make their plantation future-proof.

Large players such as Nestlé also run programmes for farmers, Veenstra explains, but here the focus is often on increasing production. “And the question is: when the big players initiate these types of programmes, is a farmer still free to sell to others?”

After harvesting, the coffee is washed, fermented in a tank for 24 hours, washed again and dried. Caravela is helping to improve this process too, so that less can go wrong at this crucial stage. Cadena: “For example, drying is usually done as quickly as possible, but we found that slow drying preserves more flavour and makes the coffee last longer. Farmers can benefit from this.”

Caravela can also help farmers to reduce the substantial amount of water required by the washing process. Cadena adds: “But you have to keep an eye out to see if the quality is affected. You can also choose not to ferment the beans and then wash them less, but this can be the expense of quality. What we primarily teach farmers is to purify the wash water afterwards and return it to the source. Some of it can also be used as fertiliser.”

Farmers can invest in their plantation, their house, a washing machine, a moped to travel to the village or education for their children with the 'extra' money they earn thanks to their cooperation with Caravela. “Farmers hope that their children will take over the plantation. We have to explore this more, but we have the feeling that our farmers' children are more willing to do so. Because they have seen that it can work well,” says Cadena.

Hopefully, in time, our farmers can even become CO2 negative.

Eight kilos of CO2 per kilo of beans

The next step for Caravela is to reduce CO2 emissions. The company wants to be CO2 neutral by 2025. Cadena: “We buy carbon credits for our own direct and indirect emissions, but the biggest challenge comes from the coffee we buy. This amounts to 90% of our emissions.” Caravela is now measuring emissions from all the plantations they work with. Cadena continues: “The footprint of a coffee farmer varies a lot from country to country: in Colombia, for example, it is eight kilos of CO2 per kilo of beans, in Mexico, it is 1.5 kilos of CO2. The farmers there are mostly elderly indigenous people who maintain a tradition of agroforestry (coffee bushes in the shade of trees) and do not use manure or pesticides.”

“We intend to reduce the CO2 emissions of all the plantations with interventions such as planting trees for shade and using less fertiliser. Chemical fertilisers are available which cost a bit more but emit less CO2. Hopefully, in time, our farmers can even become CO2 negative, and then they can sell carbon credits themselves. One of our farmers on the Galapagos Islands has already achieved this.”

Hivos-Triodos Fonds

Providing value chain finance

From the time that Caravela buys beans from farmers, it can take up to eight months before the company receives money from the roaster. Hivos-Triodos Fonds provides a value chain loan to Caravela to bridge this interim period. The loan is specifically for purchasing coffee in Peru and Mexico, where environmentally sustainable coffee cultivation is common. Nelleke Veenstra: “This value chain loan enables Caravela to pay farmers a fair price immediately upon delivery of their produce. Farmers can use this money to make their plantations future-proof.”