The COVID-pandemic and the war in Ukraine are extreme events that are testing investors, policymakers, and households’ adaptability to unexpected shocks. These shocks are causing long-term shifts in military spending and the energy markets, but also geopolitical fragmentation and perhaps even a new era of restrictive monetary policy. But undoubtedly one of the more undesirable shifts is the set-back in the progress of wellbeing as can be seen in the deteriorating progress of many of the Sustainable Development Goals.

How are emerging markets dealing with higher food and energy prices?

In many emerging countries fiscal policy had been scaled back after the pandemic but is now being stretched to its limits again as governments try to reduce the impact of the higher energy and food prices. And this is understandable; in emerging markets food and energy can weigh up to 50% in the consumer basket having a considerable impact on the purchasing power of households when prices rise. To make matters worse, the Ukraine war triggered food shortages for the world’s poorest people.

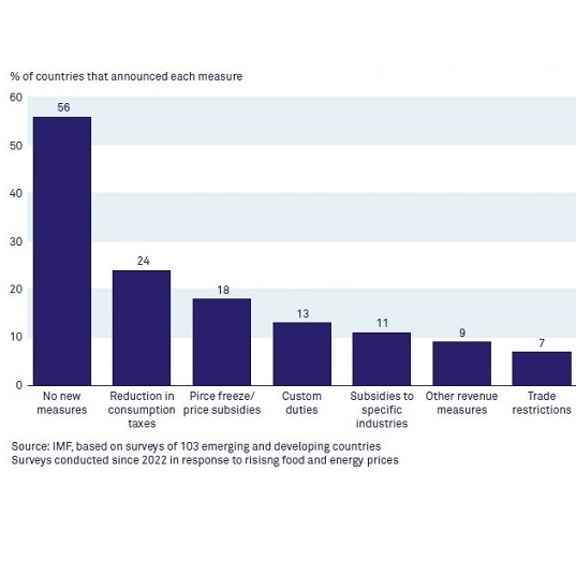

Already before the war, a large group of emerging markets was relying on subsidised food and energy. Fiscal spending had to be increased further, to compensate for the recent surge in food and energy prices. Others have for the first time adopted measures to compensate for high inflation, including the reduction of consumption taxes and introducing caps on fuel prices. Obviously, commodity exporters have been better able to limit the impact than commodity importers. No matter how understandable they are, these subsidies leave less room for other highly necessary investments in the future, for instance in education and meeting climate commitments.

Can emerging markets tackle inflation without too much pain?

Central banks in advanced economies are determined to fight inflation and are tightening their monetary policy at a faster pace than expected, even if this comes at the cost of a recession. Central banks in emerging markets are following a similar course, but lately in smaller steps. In total, around 90 central banks have raised their policy rates this year.

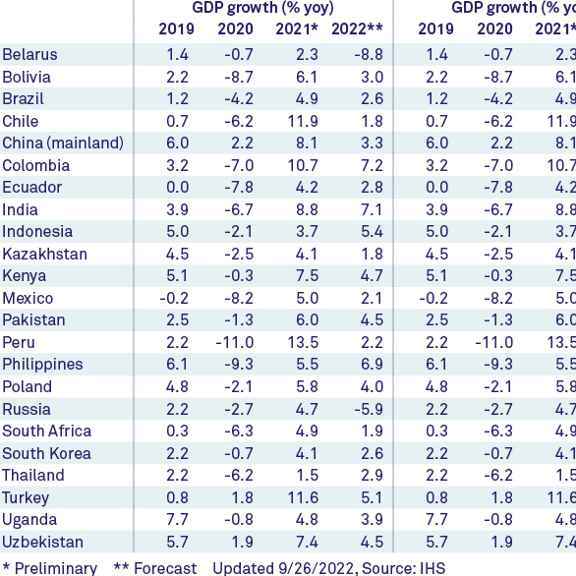

But there is a lot of divergence across countries and a growth rotation is taking place. The US, China and India continue to support a modest lift in global growth this year, while Europe is flirting with a recession. In fact, India has overtaken the UK as the world’s fifth largest economy. Although China is still dealing with the COVID drag and a fragile property market, it is showing an improvement in economic activity in the past couple of months. Additionally, China’s authorities have room for additional support given the low inflation levels.

Many commodity exporters, including Indonesia and Malaysia, have fared well in the first half of 2022, and have reported stronger growth and lower inflation levels than other emerging economies. However, the smaller commodity importing countries, including Myanmar, Sri Lanka, and Pakistan, that were already contracting and had difficulty tackling inflation before the war are facing deep recessions and double-digit inflation.

If the war in Ukraine does not take a new dimension, global inflation should start easing over the next twelve months on the back of monetary tightening. And this is necessary because high inflation exacerbates primarily the wellbeing of those living in poverty or on the brink of poverty.

What are the downward risks for emerging markets?

Our baseline scenario for emerging markets remains that of low GDP growth and inflation slowly falling in the coming quarters. Average inflation will remain above central banks’ targets in the near-term, assuming that monetary tightening and complementary measures will be sufficient to tame inflation. Recurrent rate hikes in advanced economies will likely limit global demand and trade. As demand declines, food and energy prices will gradually come down again. And although an energy crisis continues to loom in the near-term, countries are finding alternative solutions in new markets and measures, including price caps, to reduce the surging energy prices.

However, the Fed’s aggressive interest rate hikes have increased recession fears. A flight to safety has already strengthened the US dollar index with its major trading partners by 20% since the start of the year. Consequently, an overwhelming number of emerging market currencies have depreciated against the US dollar. This has resulted in higher import prices, stronger inflation pressures, and higher debt burdens as central banks that support their currencies through interventions are occasionally forced to deplete their international reserves.

These developments have increased the downside risks to our base scenario. The potential for policy mistakes is large and there are strong limits to the relief governments and central banks can provide in stressed financial markets. If the credibility of central banks to fix inflation is lost, this will, only make the dollar stronger and the pain for emerging markets larger. This negative scenario must be averted, because the poor will largely bear the brunt of these developments.

Are emerging markets in the current situation still attractive to invest in?

From an impact perspective, investing in emerging markets is more relevant than ever. Emerging markets are home to more than three-thirds of the world population and a set-back in the sustainable development goals will have considerable and broad spill-over effects. Not only on account of potential migration flows and environmental degradation resulting from unorderly exploitation of natural resources, but also because social unrest, resulting from a deterioration in living conditions can affect trade and the normal functioning of markets.

Countries that are at an early stage of development are more vulnerable to risks than developed countries but excluding them from funding would mean that they are being denied the capital they need to continue developing. Understanding country risks is therefore crucial to adopt the necessary mitigating actions. But there are other risks, including geopolitical risks, that transcend the national boundaries. The only proper response is making those countries more resilient. And time is ticking. International support will become more critical in the search for sustainable development. Emerging markets will have to work hard to become creditworthy, and private investors will have to do more to support emerging markets in their transition, or we will all suffer the consequences.

How can emerging markets become more resilient?

Past experience shows that the resilience of certain emerging countries often reflects a combination of policy choices taken, generally in a benign international environment. Countries, including Uruguay and Botswana, that have capitalised the gains from trade by focusing social protection and internal integration, and developed high-quality institutions, are success stories.

But obviously the level of development of a country matters.Countries that are lagging far behind the sustainable development goals have a more difficult task and making progress cannot be done without international support. How will these countries otherwise be able to seize the opportunities of major transformations, including climate and digital transitions? For these vulnerable countries, struck by COVID and a war and with limited access to capital markets, drawing on collective strength is the only way forward towards a more resilient future.